In April (2002) Holger Czukay came to Osaka to kick off the Japan leg of a world tour and we became the latest subjects of this incorrigible experimenter. The show that he put on at Club Karma was the first of a series of concerts that were a 35 year retrospective spanning his earliest work with seminal 70s art rock meisters Can, his solo career, many collaborations, and his recent work drawing in influences from the techno music that he had already influenced. This article was originally published in the May 2002 issue of Kansai Scene magazine.

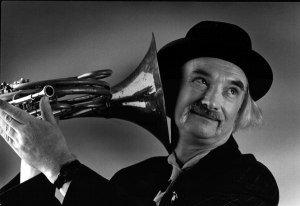

You may never have heard of Holger Czukay yet he has been one of the biggest influences on music since Bill Hailey learned how to tell the time and Elvis discovered his pelvis. In April he came to Osaka to turn us all into guinea pigs, and Kansai Scene demanded of him “Wer zum Teufel ist Holger Czukay?”

I was late for the interview. It was three a.m. in Cologne and Holger Czukay was waiting up to speak to me. My number one tape recorder had seized up, the number two recorder was fried, and the number three recording device was just dead cranky. Sweaty panic beaded my forehead. I apologised to Holger and sheepishly explained that our recording devices were not as sophisticated as his. “My recording machines have always been pretty rudimentary,” he replied patiently.

It was an odd concept that the man credited with inventing sampling and with dragging electronic music out of its avant garde closet and into the rock mainstream had merely rudimentary recorders. It was odder when you listen to the carefully layered, meticulously textured recordings. Holger Czukay was a student electronic experimenter Karlheinz Stockhausen he influenced the original punk bands with his rough minimalism, has been cited as an influence by the Buzzcocks, the Fall, PIL, Sonic Youth and Stereolab among others, he has collaborated with the Edge David Sylvian, Jah Wobble and Brian Eno, has composed countless scores for TV and film— what is he doing with merely rudimentary recording devices?

Yet the remark is very Holger Czukay, and is revealing about the way he works and about his personality. Speaking to him or listening to his recordings you are struck by his quiet modesty, his pragmatism, and his fascination with sound. He has a surreal and mischievous sense of humour, yet when talking about his work he is very serious indeed. As a youngster growing up as a refugee from Danzig in post-war Germany his sole ambition was to be a composer of serious music. At the age of 16, on hearing at music school that to be taken seriously as a composer you have to show signs of being a prodigy before you are 15 years old, he thought “One year too late!” and with the simple can-do optimism that characterises much of what he does, he decided to become a conductor instead. He has succeeded in both ambitions, though perhaps not in the way he imagined when he was 16.

For all his evident care for his work, and his regard for Germany’s heritage of classical music, his life and music are created out of improvisation, spontaneity, and experimentation. He tells you that he sleeps when he is tired and eats when he is hungry and otherwise seems to spend all his time following his instincts in the studio. And here of course, he was speaking to me at 3 a.m. with no sign of fatigue. You can imagine him without the constraints of the routines and workaday demands that govern the rest of us, working and following his imagination as it takes him and attending his other needs as they take him — a free spirit haunting and exploring a universe of sound and oblivious to the differences between day and night, or the days of the week. He explained to me, “in the beginning with Can we wanted to become independent and free this was the first thing we wanted. We didn’t want to have a producer from the record company we just wanted to be independent on our own. This is more or less the thing which accompanies me my whole life from childhood on”.

When the musicians that became Can — Michael Karoli, Ermin Schmidt, and Jaki Leibezeit — first came together they had no idea what kind of music they were going to play or what kind of band they were going to be. They only knew they were going to make music. Without rehearsing, they booked a their first gigs, improvised their way through a set and only then decided they were a rock band. In those early days, the live improvisations could last 12 or more hours.

The early Can albums have a crafted quality about them that belies the fact that they were born of studio improvisations without even the aid of a multi-track recorder. This period and these works were obviously the best period for this collaborative, improvisational method. If one person fluffed a note or played too loud the whole recording would have to be binned. Holger likened the experience to playing in a football team. “To play in such a group like with Can means you have to be trained to listen to the other one what he’s doing and immediately reflect on that. Football players are perfectly doing that. Nobody knows where the ball will be in the next moment but the teams are trained to get into the goal without knowing what happens next.”

In this period he developed techniques for integrating with the conventional instruments found sounds, samples, and synthesised sounds — this in the 70s before synthesisers or samplers. The band broke more new ground by creating rhythms unfamiliar in rock at that time after listening to African and Asian music — even Japanese Noh. The albums of this period — and principally Monster Movie, Tago Mago, Ege Bamyasi — still sound fresh and surprising today.

He blames the eventual break up of the band in the late 70s to a loss of this spontaneity brought about by the acquisition of sophisticated multi-tracking recording equipment. Suddenly the individual members of the band wanted to record their parts separately in order to get them just so. The work lost its qualities of impulsiveness and teamwork that had distinguished it and they went their different ways amicably.

They would get together from time to time to make new recordings – they recorded another album as Can (Rite Time) with their original singer Malcolm Mooney in 1986. Holger collaborated with other members of the band on his solo projects but he assumed the mantle of experimenter and improviser.

The break up of Can marked a second phase of improvisation, that of editing and rearranging new and old material into different forms, some of which made it onto vinyl, most of which didn’t. Here he was focussed on developing technology and methods for creating new sounds and new forms. I asked Holger whether there were plans to re-release his original albums he laughed and told me his cache of unreleased, unfinished stuff dwarfed his catalogue of recordings. Some of this material in the cache dates back to the earlier improvisations with Can and is a stock of material he returns to time and again to update and rework as the mood or the needs of the moment take him.

Holger disappeared into his studio for ten years urgently developing his ideas and trying to find out how much of the unlikely was actually possible. He forgot about the rest of the musical world until coaxed out by a journalist who insisted there was something going on Holger really needed to know about. He was taken to a techno event and was stunned. While cloistered away, a new generation of musicians had seized on electronic music; had effectively continued work he had started and had taken the form new and exciting places.

The techno music that Czukay discovered was not just a fertile ground of invention, it was very much concerned with issues close to Holger’s heart: rhythm, texture, simplicity, found sounds, and was a direct descendent of the punk ethic of minimalism and of doing it for yourself. There is also communality and impulsiveness in the techno world that must have been very familiar to the man from his Can days.

The oeuvre he helped to create in turn influenced him, and Holger has imported forms and techniques from techno into his work. A few years ago at the age of 60 he went on tour with a DJ, Dr. Walker.

They say you can’t teach an old dog new tricks. Holger Czukay has obviously never heard that expression. The new technologies have enabled him to find new means and opportunities for developing his work. He concedes that digital technology has taken some of the ingenuity and make-do from the process of creating, but points out the huge benefits. There is more scope for manipulating sound and the internet provides more chances for collaboration and community.

He started a project through his web site designed to be an open collaboration. Participants could download the work in progress, add their contribution and upload the growing piece back to the site. He says the response to this project was “fantastic, absolutely fantastic”, and three pieces were created. You can hear them at the site (now removed). Can was a synergistic coming together of strangers: the internet is more so because an unlimited number of people can be involved — and even after playing you don’t know who your collaborators were.

And of the future? Is he going to take a break as he heads for retirement age? Not on your nelly. Incorporating the functions of both DJ and musician, he plans to create a new kind of web-based show where musicians all over the world can play together simultaneously, while on stage he gathers the sound into its final form, making himself the digital conductor of a virtual orchestra of people who have never met or played together before.

“Are you a musician, a technician, or an experimenter” I asked him.

“I’m an open-minded person”, he told me.

So, who the hell is Holger Czukay? Er ist genau derjenige, der er ist — he’s the man, that’s who he is.

Post script: Holger Czukay passed away on September 5, 2017