This article was first published in the June 2012 edition of Kansai Scene magazine.

Chris Page spends an afternoon at the cinema and asks, is Yu Irie the coolest director in Japan?

The man

Kansai Scene was treated to a screening of Saitama Rapper: Roadside Fugitive at independent Cinema 7 in Juso. The theatre was packed and it was standing room only at the back for the overflow of moviegoers, KS included.

Afterwards, while the stars of the film met with fans in the street outside, KS sat down for a coffee with the film’s director Yu Irie in a nearby cafe.

Irie was quiet and relaxed and spoke with a business-like eloquence about his films. And there was a lot to talk about.

Roadside Fugitive is the third in a series of films about wannabe rappers (see sidebar). Three rap-themed films? What’s with the rap? At first, Irie blandly replied that he liked hip-hop so it was an easy vehicle. He then went on: “In rap you don’t have the usual inhibitions to expression. You can express ideas you normally wouldn’t be able to.”

It’s not just rap that enables an artist to articulate difficult ideas, so does moviemaking and themes of betrayal and disillusion are strong in SR3 — are these a condition of modern Japan?

“There is a lot of anger in the film. It comes from a lot of things, but in part it comes from the earthquake of 2011. It was with that event that a lot of things came out that we didn’t know.” Irie explained that the government and the nuclear industry had been lying to people for a long time, and continued to do so even as the Fukushima reactors melted down. The 2011 disaster does not figure directly in the film but the sense of betrayal and disillusion it engendered does.

There is a strong thread of social commentary. The film’s bad guys are quite startlingly bad — they bully, humiliate and exploit, seemingly with relish, and are quick to turn on the violence. This viewer was left with the impression he was seeing a dark and scary side of Japan he had hitherto missed.

Tokyo, the big city of bright lights, is a place of hopes and ambitions fulfilled, but most of us never get there, Irie tells us. It’s impossible not see the story as a representation of the frustration of an over-mediated generation lacking faith or direction in conventional lifestyles and aspirations.

Disaffection is not a phenomenon we easily associate with Japan, but here it is, a big, loud cry in movie form.

Comparisons with Curtis Hanson’s 8 Mile are inevitable, but Irie brushes them aside. These are two different films each reflecting its own society. 8 Mile deals with poverty and racism, Roadside Fugitive deals with other themes. While Hanson’s characters are trying to rap their way out of the ghetto, or at least garner some respect, Irie’s characters are trying to escape from a mundane and cloying life.

Cinematographically, Irie is clear, the two films are different beasts. Irie insists that 8 Mile was a “cool” movie and he didn’t want to make a cool movie. What he means by this is that 8 Mile is a slick, big-budget production, faithful to the mores of mainstream filmmaking. Whatever the strengths of the story, it was made a movie kind of movie. With Roadside Fugitive Irie has eschewed convention to attempt an ultra-realism.

“In 8 Mile, people are talking or walking down the street and suddenly you get background music. That doesn’t happen in real life. I have used no background music and none of the usual filming tricks to create effect. There’s music in the story but it’s where you find it in real life: on the stage.”

Disarmingly, the director tells us his film is “deliberately uncool”. It’s made with hand-held cameras and a minimum of technical artifice, which gives it a sort of fly-on-wall perspective for the audience.

Irie makes use of some extraordinarily long single shots, each seemingly several minutes in length. “I’m not trying that again,” he said flatly. These shots are employed at the emotional and dramatic climaxes of the film taking us through the final and dramatic fall of the protagonist, Mighty (Eita Okuno — see sidebar). They have the effect of putting the viewer right there in the middle of the character’s crisis and contribute to the suspense. However, these long shots are extremely demanding for actors and crew.

Okuno, more than the other actors, is required to sustain a considerable emotional intensity and convey his extreme state of mind, while doing some demanding physical work without any pause for breath. Obviously, this kind of scene is just one take. This is why Irie is now reluctant to try this technique again.

The approach works. As the takes go on and on, you find yourself holding your breath with anticipation and the effect is one of immediacy. You are right there in the action alongside the Mighty and his pals Tom and Ikku and the scary yakuza. Irie says he was aiming for “raw”. Raw is certainly what we get.

Irie now has three acclaimed rap films on his growing CV. So what next? The man will not be drawn, but if he maintains the impetus he has picked up with the Saitama Rapper films, his will be a career to watch.

The rap

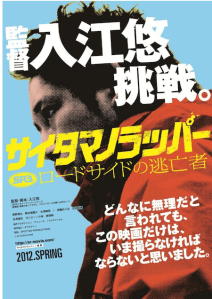

What: Saitama Rapper: Roadside Fugitive, aka, Saitama Rapper 3, 8000 Miles: Roadside Fugitive, or Roadside Fugitive, or サイタマノラッパーロードサイドの逃亡者, or just SR3, depending who you are talking to.

When: very much now, if you see what I mean.

Where: not simply everywhere — you have to look for this one. But we’ve made it easier with some pointers below.

Why: Saitama Rapper: Roadside Fugitive is the latest film from Yu Irie, a rising star in Japan’s film industry.

Roadside Fugitive is the third film in the Saitama Rapper series, which kicked off in 2009, with a film that according to one blogger wag was not so much low-budget as no-budget, with reported production costs of a tiny two million yen. The film tells the story of three young men trying to break out of what they consider to be a dull rural experience and get to the bright lights of the big city as professional rappers.

They don’t make it, and at the end of the film we see one of the characters, DJ Mighty (Eita Okuno), striking off on his own. The second film in the series takes up a different story with different characters, an all-girl rap act. The third catches up with the original characters three years down the road. DJ Mighty is still in Tokyo pursuing his dream and in the rap battles shows some real promise until he falls in with a bad crowd who, shall we say, don’t have his best interests or anybody else’s at heart. In a parallel story we see his two hometown rapper pals Ikku (Ryusuke Komakine), Tom (Shingo Mizusawa) still pounding the beat of provincial talent contests and rap events, still trying to get their own break.

Where Mighty’s story is dark and tragic, the tale of his pals is lighter and comedic and the two tales complement each other perfectly taking us by different routes to a powerful denouement.

Tight plotting, snappy dialogue and compelling characters, all presented with some very clever cinematography make this a must-see.